Xi Xi’s poetry defies simple categorization. In her poems, clouds can organize an industrial strike and hum Beethoven, a young child can grow up to become a water heater, and the progenitor of us all might very well be a black butterfly. She is equally at home writing about the Beat poets and Tang masters, French New Wave film and traditional Chinese art and music.

Xi Xi (also known as Sai Sai), pseudonym of Cheung Yin, is one of Hong Kong’s most beloved and acclaimed writers, as well as a stylistic innovator across genres. She has published two poetry volumes, seven novels, twenty-one short story and essay collections, and one stand-alone novella, and many of her books have been reprinted in Taiwan, Hong Kong, and mainland China. She also has penned numerous newspaper and magazine columns, translations, and screenplays, and she is a pioneer in 1960s Hong Kong experimental filmmaking. As her fame as a fiction writer and essayist has eclipsed her poetic achievements, many of her readers are unaware that she actually launched her writing career as a poet.

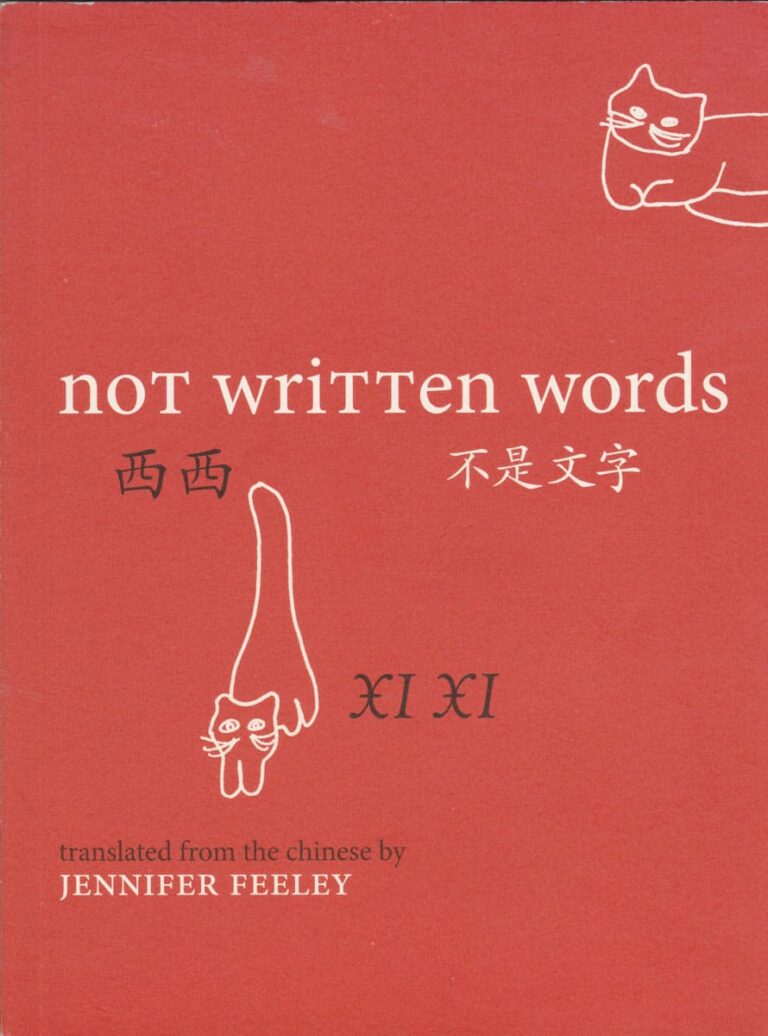

Her attitude toward literature, and life in general, perhaps is best epitomized through her chosen penname. For Xi Xi, the graphic quality of the Chinese character xi 西 looks like a girl in a skirt playing a game similar to hopscotch. Duplicating the characters side-by-side calls to mind the frame of a film, with the girl hopping from one square to another. This anecdote encapsulates the playfulness and creativity that one finds in Xi Xi’s work and underscores the centrality of childlike perception and visuality in her oeuvre. Much of her writing reinvests the mundane with unexpected meanings, encouraging the reader to experience the familiar in new ways.

The second eldest of five children, Xi Xi was born in Shanghai in 1937 to parents of Cantonese ancestry. She immigrated with her family to colonial Hong Kong in 1950, placing her among the first generation of authors to have grown up in the territory. Her father was an inspector for the Kowloon Bus Company and coached soccer on the side; Xi Xi frequently accompanied him to watch matches, instilling in her a love of the sport from childhood. Her family struggled financially, so after completing her secondary education at an English-language high school, in 1957 she enrolled at the Grantham College of Education, where tuition fees were waived and a job was practically guaranteed upon graduation. After college, she worked as an English teacher in a government primary school, campaigning for teachers’ rights during the 1970s. Due to a surplus of teachers in Hong Kong, in 1979 she accepted an early retirement offer so that she could write full-time, though occasionally she filled in as a substitute teacher to supplement her income.

Living in Hong Kong and being multilingual (in addition to her fluency in Cantonese, Mandarin, Shanghainese, and English, she studied French for several years and is self-taught in Spanish) has put Xi Xi in dialogue with world literature and culture. She cites children’s literature, film, and contemporary Latin American and European literature as the main influences on her writing, displaying a special fondness for magic realism and the Nouveau Roman. She has experimented with most sub-genres of contemporary literature, including realism, modernism, post-modernism, magic realism, allegory, legends, and fairy tales. There is a predilection for intertextuality in her work, as in her early poems, which borrow from children’s stories and fairy tales, or her short story “Bus,” which pays tribute to Raymond Queneau’s Exercises in Style and reads like a long prose poem.

Xi Xi was drawn to poetry from a young age. Her first publication, a sonnet entitled “Lake,” was published when she was only fifteen; in hindsight, she dismisses it as singsong nonsense, remarking that she hadn’t even seen an actual lake at that point. Yet despite the self-deprecating evaluation of her early work, as a teenager she won first prize in a poetry competition, and throughout the 1950s, her writing was featured in a variety of periodicals.

Through her involvement with the newspaper the Sing Tao Daily, as a student, Xi Xi came to know emerging authors Wucius Wong and Quanan Shum, and they in turn introduced her to Wai-lim Yip. During the 1950s and ’60s, Wong, Shum, and Yip helped forge a new literary culture that drew upon classical Chinese poetry, modernist Chinese poetry from the 1930s and ’40s (which was banned in both China and Taiwan at the time), and Western modernism. These authors were wrestling with issues unique to Hong Kong, such as cultural identity, consumerism, and British colonization. All three became Xi Xi’s literary mentors. She recalls being so impressed by one of Yip’s poems that she found her own poems laughable by comparison and lost her nerve to keep writing poetry. She thus turned her attention to other genres, giving rise to her career as a fiction writer, composing poetry only sparingly.

The ’60s came to be known as Xi Xi’s cinematic decade, during which time she directed the experimental film Milky Way Galaxy, wrote movie scripts for the Shaw Brothers Studio under the pseudonym Hai Lan (including a 1967 adaptation of Little Women), participated in a cinema club, and published reviews of Hong Kong blockbusters and European art films. Traces of cinema can be found throughout her work, including her 1964 prose poem “At Marienbad.” A reflection on Alain Resnais’ 1961 French New Wave masterpiece Last Year at Marienbad, the poem draws on themes and images from various films, including works by Cocteau, Bergman, and Chaplin, adopting montage as a technique for writing poetry.

The face of the afternoon paper. A stampede of fenced-in cattle. Green light. I race against the sick Futurist sun. All figures are .

Walk down the hallway. Run into someone hawking wild strawberries and singing strange songs. A girl rolling a copper hoop. A bell rings thrice. A poster paster appears. Cocteau stands behind a harp. Staring. Watching me, glancing past.

The evening paper covers the face of the afternoon paper. I run relays run obstacles. The hands of the police. Every clip-clop every two wheels intertwining every cross. Give me an anchor. Give me a mountain.

Xi Xi’s writing flourished during the ’60s and ’70s. From the 1960s to ’80s she composed more than ten columns on literature, film, fairy tales, music, and art, in addition to short fiction, a novel, and occasional essays. She also served as the poetry editor for The Chinese Student Weekly. Her debut short story, “Maria,” about a Belgian nun in the Congo during the political upheaval of the early 1960s, was published in 1965 to great critical acclaim, followed by her 1966 novella East Side Story (based on West Side Story). The 1970s saw the publication of her groundbreaking novel, My City (first serialized in 1974 and released in book form in 1979), one of the first literary works to portray Hong Kong from the viewpoint of its ordinary residents. She also edited the influential non-commercial literary journals Thumb and Plain Leaves, the latter which she co-founded with friends and expanded into a non-profit publishing house that continued into the ’80s. In 1982, Plain Leaves Press published Xi Xi’s first poetry collection, Stone Chimes, comprised of 40 poems.

In their reviews of Stone Chimes, critics noted that while classical Chinese poetry is replete with laments, Xi Xi prefers to use comedic effect, as she believes that literature is filled with too many monotonous tragedies. With its short lines, plentiful rhymes, catchy rhythm, repetitions, simple language, and humor, “Butterflies Are Lightsome Things” reads like a childhood playground song, yet it also is a parable on attachment and letting go.

so gradually I’ve come to see

why butterflies can flutter by

cuz why cuz why

cuz butterflies are lightsome things

because because

butterflies lack heartstrings

As Xi Xi is careful to point out, content-wise, most of her work is serious, and her use of comedy as a technique shouldn’t be mistaken for comedy itself. While numerous poems from Stone Chimes may come across as light verse, marveling at the mundane with the awe of a child’s imagination, they subvert readers’ expectations with their sharp insights.

By the early ’80s, though Xi Xi already had earned several literary awards in Hong Kong, her fame did not truly catapult until her short story “A Woman Like Me” garnered Taiwan’s prestigious United Daily fiction prize in 1983, earning her an enthusiastic following throughout the region and prompting fans to mistake her for a Taiwanese writer. Throughout the ’80s, she published multiple collections of short stories and essays and one novel. After mainland China implemented reforms and opened up, she compiled and edited fiction by prominent mainland authors such as Mo Yan to introduce their work to readers in Taiwan and Hong Kong.

In fall of 1989, Xi Xi was diagnosed with breast cancer. Though the illness took a toll on her health, she recorded her struggle in her 1992 semiautobiographical novel Mourning a Breast (adapted into the film 2 Become 1, produced by Johnnie To). Nerve damage from the treatment left her with limited mobility in her right hand; undeterred, she taught herself to write with her left, inspiring graphic novelist Chihoi to use his own left hand to draw the comic adaptation of one of her short stories. In spite of these major health issues, Xi Xi’s exceptional literary productivity has continued through the present with the publication of numerous short stories, prose, novellas, and novels.

As a form of physical therapy, since 2005 she has turned her attention to arts and crafts, constructing miniature houses and sewing handmade cloth dolls, puppets, and stuffed animals, resulting in her award-winning essay and photograph collections The Teddy Bear Chronicles (2009) and Chronicles of Apes and Monkeys (2011). The former is comprised of essays about and photographs of her handcrafted teddy bears clothed in costumes from various historical periods, the bears representing famous real and fictional figures such as heroes from the sixteenth-century novel The Water Margin, the woman warrior Hua Mulan, the philosopher Zhuangzi, and Beauty and the Beast. Her travels to zoos, conservation centers, and rainforests throughout Asia resulted in the latter volume, which uses 51 hand-sewn puppets, along with illustrations by Ho Fuk Yan, to chronicle the relationship between humans and simians. Xi Xi hopes that The Teddy Bear Chronicles will make traditional culture more accessible to a younger generation and that Chronicles of Apes and Monkeys will raise public awareness of the importance of protecting animals and nature.

During the past three decades, Xi Xi has continued to rack up literary prizes, most recently Taiwan’s 2014 Hsing Yun Global Chinese Literary Award. She was named the Writer of the Year for the 2011 Hong Kong Book Fair, is the subject of two documentary films, including Fruit Chan’s 2015 My City, and protestors discussed her work during the 2014 Umbrella Movement, attesting to her enduring relevance. Her essay “Shops” has been incorporated into Hong Kong’s official high school curriculum in Chinese literature, making her name well known among secondary school children. Currently, she and her close friend, the famed critic Ho Fuk Yan, have been writing dialogues on science fiction films and novels.

In 2000, Xi Xi published her second poetry volume, The Selected Poems of Xi Xi: 1959–1999, comprised of three sections and 106 poems, with one-third of the content culled from Stone Chimes. In the preface, she explains that she resumed writing poetry in the ’80s for two reasons. Firstly, she learned how to use a computer, and as she became more comfortable with inputting Chinese characters, her poems grew longer and longer. She playfully captures this newfound love-hate relationship with technology in “Aria,” a poem for her computer. Secondly, she’d become increasingly frustrated by the lack of intelligibility of numerous poetry collections and decided to create her own style by ignoring literary trends and other people’s opinions. The result is a body of poems that is both distinctive and versatile.

Not Written Words marks the first collection of Xi Xi’s poems available in English. It spans a poetry career of more than four decades, from 1961–1999. It includes two of her earliest poems (both from Selected Poems), 15 selections from Stone Chimes (12 of which are reprinted in Selected Poems), and 28 works from Selected Poems. It follows the order of the poems from both volumes, which is partly chronological and partly thematic. The first 17 poems were written between 1961 and 1982, and the rest during the ’80s and ’90s.

Xi Xi’s poetry, like most of her work, is anti-establishment, her rebelliousness manifest in the form of artistic expression. Her subversion of language and conventions has prompted Ho Fuk Yan to coin the term “urchin style” to describe her writing. Urchin style is child-like, mischievous, humorous, and at times irreverent, as illustrated in the following lines from “Can We Say”:

Can we say

an excellency of ants

a caucus of cucarachas

a hamlet of hams

a sandwich of heroes?

Can we say

a head of academic deans

a clutch of regional inspectors

a stable of generals

a tail of emperor?

The poem mismatches nouns with incorrect classifiers: ants and cockroaches are preceded by honorific measure words, while high-ranking officials are counted with quantifiers used for livestock and fish. Social hierarchies are reversed, and even the emperor is lampooned. “Can We Say” asks us to rethink language and the concepts behind it.

Xi Xi’s love of language games is palpable throughout her poetry. Her poems mine the richness of both the aural and written aspects of Chinese to craft clever wordplay, as in “The Merry Building,” which delights in the confusion of a pair of near-homophones, “This is Not a Poem,” which pays homage to Belgian surrealist René Magritte, and “A Striped Tiger in a Thicket of Green Grass,” where the “tiger” in the poem is represented by the character 王, which resembles the stripes on a tiger’s forehead. Meanwhile, the limits of language are questioned in “Sonnet,” where the speaker initially claims that the written word is the one thing she has a handle on, the poem then concluding with her disbelief in the power of the written word and its clichés. Similarly, in “What I’m Thinking of is Not Written Words,” she ponders language’s shortcomings:

Words can be embellished

Well-versed at subterfuge

Some people’s words are tangled

And tongue-tied

And words have seven types of ambiguity

They speak obscurely

Pointing west

But heading east

Xi Xi’s writing has been labeled fairy-tale realism for its blending of the real and the fantastic: while her work is grounded in the reality of everyday life, fairy tales provide her the necessary distance from reality to observe it. Yet just as she often uses comedy as a technique without writing actual comedy, her work is reminiscent of fairy tales without being cartoonish. She uses a light touch to broach serious topics, as in “Motionless Clouds,” where clouds protest the opening of a desalination plant by organizing a strike.

By day

they happily doze off

content to catch the occasional whiff of coffee

By night

they count neon lights

and hum Beethoven

From time to time they remember their obligations

but only punch in from 9 to 5

launching a work-to-rule campaign

scattering two or three drops here and there

to water nearby chimneys

“Motionless Clouds” subverts classical Chinese poet Tao Yuanming’s poem of the same name. While Tao’s piece is about a flood, Xi Xi writes about a drought, using fairy-tale realism to comment on environmental and labor issues.

The first book Xi Xi read in her youth was an illustrated version of Snow White. She was particularly fascinated by pictures of the characters’ clothing, which reminded her of soccer players’ knee socks. The writings of Hans Christian Andersen and Oscar Wilde’s The Happy Prince are some of her favorite works, and she believes in the contemporary relevance of fairy tales, using Cinderella as a metaphor for Hong Kong in her short story “Glass Slippers.” Poems such as “Snow White and the Princess,” “A Tale about Seeing,” and “Many a Lady” speak to her love of children’s literature. Under Xi Xi’s pen, however, there is a twist. The “you” in “Snow White and the Princess” literally turns into Snow White, with “black hair / Beset by snowflakes / Thousands upon thousands of strands / A gray celestial net that no one can escape.” In “Many a Lady,” women eschew Prince Charming in favor of a Taoist immortal who can remold their bodies, thereby allowing them to give Adam back his rib and become independent of men.

Fairy-tale realism and her urchin style only represent one dimension of Xi Xi’s poetry, however. Social consciousness is present even in these early poems and becomes more acute in her later work, where she mostly forgoes her earlier comedic technique. Her own vantage point as a writer on the margins contributes to her awareness and empathy toward the vulnerable and peripheral. In “Driving through Palestinian Refugee Camps,” the rhetorical “What’s home without a country” might be equally applicable to Hong Kong citizens as it is to Palestinians.

As far as the eye can see, overcrowded camps once filled with tents

Are now crude brook houses roofed in tin

Freezers in winter, ovens on summer days

What’s the point of better housing

What’s home without a country, so you gather all your might

To fight for a homeland of your own, yet we still

Call you all terrorists, annihilate every last one of you

Your voices we don’t hear

Your religion is not within our understanding

Your language needs to be translated and retranslated

Still there’s no guarantee you’ll gain entrance to our world

Her poems explore both home and the world with a keen sensitivity toward people and things that are easily overlooked, such as an elderly letter writer who lives in a neighboring rundown building, Syrian residents who are relocated in the name of government resettlement, Thomas Mann’s ailing wife Katia, and a butterfly that uses pollen to conquer a fearsome crocodile.

Xi Xi is very much a Hong Kong author, and her poems see the city from uncommon perspectives. “Fast Food” celebrates the liberation of dining out in Hong Kong’s many cafés. “The Letter Writer” sketches a glimpse of the neighborhood where Xi Xi has lived for more than forty years, taking as its subject an old woman with a bygone profession. “Supermarket” imagines Allen Ginsberg strolling through the districts of Mong Kok, Central, or Causeway Bay. Meanwhile, “Pebble” contemplates the Hong Kong handover from the viewpoint of a stone isolated in the Gobi Desert, remarking, “1997 / or 9971 / what’s it / to me”. In poems about her travels to the Middle East, Hong Kong is associated with China, as in the following lines from “Pigeon Rock”: “China opposed the U.S.-British bombing of Iraq / Which makes you an ally of the Arabs.” Other poems allude to her involvement in political demonstrations in Hong Kong, making them relevant to recent events.

The content of her poetry is diverse. With each literary work, she aims to offer readers something new, whether in terms of content or technique. Nevertheless, certain topics recur: an interest in ancient Chinese culture, a love of children and animals, a concern for the environment, extensive travel experiences, and a curiosity toward the malleability of language. Her poems are full of hidden clues, brimming with allusions, puns, and references to other works, including her own. “The Merry Building” shares a connection with her novel of the same name, and “I’m Happy” is featured within her novel My City.

Although she is a Hong Kong poet, Xi Xi primarily writes in standard written Chinese, with only the occasional Cantonese phrasing. Stylistically, the ordinariness of her poetry reflects the ordinariness of 1970s Hong Kong poetry. She consistently uses plain and understated language, yet her poetry is nevertheless provocative and philosophical. Her early poems are light, whimsical, and abundant in musicality and wordplay (while formal prosody is not part of her poetics, many of her works luxuriate in rhyme), with deceptively simple lines. Her later poems are longer, denser, and more conversational, at times resembling essays or commentaries. She pushes language past its limits, crafting poems that don’t always seem like poems, inviting us to broaden our ideas of what counts as poetry. She is one of the most experimental poets writing in Chinese, and much of her poetry hinges upon language itself—homophones, rhymes, the subversion of idioms and grammar, and puns on Chinese characters.

This aspect of Xi Xi’s poetry makes it both challenging and delightful to translate. Recreating the tone, sound, and texture of her work entails much more than word-for-word translation. Where she creates semantic dissonance, I respond with similarly jarring phrasings such as “an ear of cabbage” or “a flock of scallions”. Where she crafts puns and puzzles, I invent analogous word games, as in my rendering of her concrete poem “A Striped Tiger in a Thicket of Green Grass,” which takes advantage of English’s own visuality to embed the poem’s striped tiger into an anagram. Where she revels in rhyme, repetition, and aural wordplay, I strive to incorporate such sound devices, though at times this decision results in slight shifts in word choice (for example, changing “beautiful” to “merry” in order to chime off of Murray). The resulting translations invite an exploration of the pliability of poetry in terms of both content and language, encouraging readers to become unshackled from conventions and rules.

In the penultimate poem in the collection, “Reading Translations of the Closing Couplet of Yeats’ ‘Among School Children,’” Xi Xi notes that all translations are transitions. In the process of bringing Xi Xi’s poetry into a landscape filled with different nuances, both the poems and the landscape itself have undergone inevitable transformations in order to accommodate her playful wit and compassionate observations within a new language and culture.

O disparate starry skies, O variant landscapes

How can we know the poet from the poem in translation?

Jennifer Feeley

June 2015